The 1960s was a time of tremendous economic expansion. It was also a time of ambitious social change, from the Civil Rights Movement to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs.

But despite the economic boom that had started after the Second World War, money was still finite, and the U.S. war in Vietnam proved a drain on funds that many wanted spent on social change at home in America.

That was the subject of a March 2022 lecture at the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum in Columbia. Francis Marion University historian Jason Kirby spoke on “Guns and Butter: William C. Westmoreland, Military Objectives, African American troops and Civil Rights.”

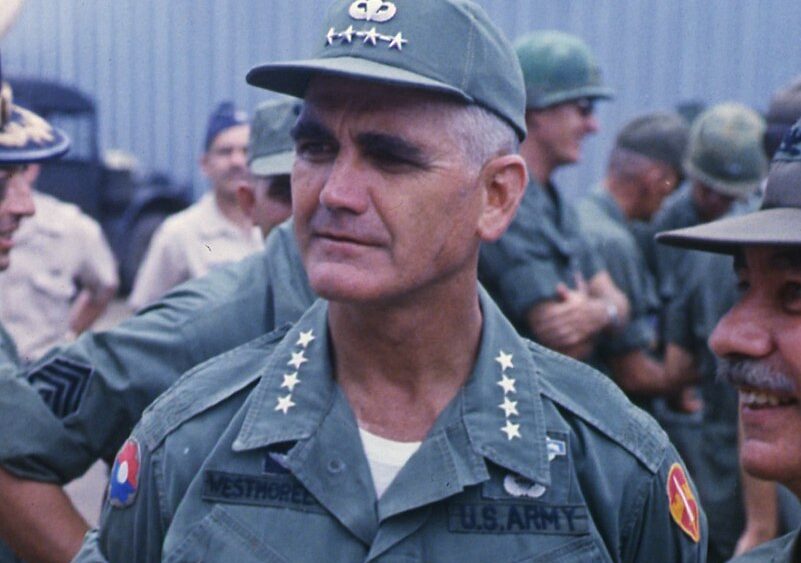

Westmoreland, who commanded U.S. forces in Vietnam from 1964 to 1968, played a central role in the topics covered by Dr. Kirby, for whom the general – a South Carolina native – has been a subject of intense study.

Kirby has endeavored to look at Westmoreland “from a different angle.” Most historians consider him in terms of his performance as a military commander, and as a polarizing political figure on the home front, in light of the antiwar movement.

“I’m basically putting Westmoreland front and center with Civil Rights and the Great Society initiatives,” says Kirby. As the man who presided over the huge expansion of the war effort from 1965 to 1968, the general “was a pivotal force on how LBJ would spend money.”

Johnson sought to enact and fund programs that would continue, and in many ways exceed, those implemented by Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal a generation earlier. The aspirations of these programs, which included the War on Poverty, were in many ways tied to those of the Civil Rights Movement, as they aimed to improve the lives of all disadvantaged Americans.

Westmoreland was also leading the nation’s largest military effort since the uniformed services had been racially integrated in the late 1940s. He was doing this while pushing for constant reinforcements in Vietnam, culminating with a total of 535,000 troops by the time he was relieved of command in 1968.

Then there was the draft, which offered exemptions such as college deferment that were more easily available to the white middle class. Thus, while the civilian population was only 11 percent African-American, as of 1967, black men made up 16.3 percent of all draftees and 23 percent of all combat troops.

As the war expanded, many younger civil rights leaders – those closer to draft age – moved away from supporting the war. This was support Johnson could not afford to lose, and Westmoreland was the man in the middle of this political conflict, both in Vietnam and at home.

Between military setbacks and the political conflict back in the states, “things got really dicey in 1968,” says Kirby.

Kirby is an assistant professor of history at Francis Marion. Originally from Kentucky, he received his PhD from the University of Georgia in 2018, and joined the FMU faculty in the fall of 2019. Courses he teaches include U.S. History since 1877; History of the New South, 1865 to present; America in the 1960s; The United States Between the Wars, 1918-1941; and the Vietnam War. He is also a certified South Carolina social studies/history teacher for grades 6-12), and serves as the coordinator of the Secondary Education in Social Studies program at Francis Marion.

Comments are closed.