The first U.S. military pilot to be shot down and taken prisoner in Vietnam was naval aviator Everett Alvarez Jr. It happened on Aug. 5, 1964. He would endure eight years and seven months of brutal captivity at the Hỏa Lò Prison, ironically called the “Hanoi Hilton” by fellow POWs.

He was alone there at first, but he would eventually be one of hundreds of Americans to be held there and elsewhere in North and South Vietnam, by either the North Vietnamese Army or the Viet Cong. Today, the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum features a display about those prisoners of war, concentrating in particular on those with South Carolina connections.

At noon on June 28, at Richland Library in Columbia, Joe Long – the museum’s curator of education – will speak about those and other POWs, concentrating on their experiences, and the folks back home who refused to forget them. The free lecture is part of the museum’s regular Noon Debrief program. Those lectures are usually presented at the Relic Room itself, but since the museum is undergoing renovation, the nearby library has generously offered a venue for the program off-site. Joe will speak in the Theater at the library.

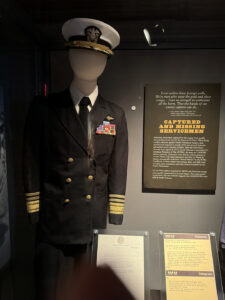

One thing Joe will talk about is the museum’s Vietnam POW exhibit, which among other artifacts features the Service Dress Blue uniform of Adm. James Bond Stockdale. He was the most senior naval officer held captive in Hanoi after his A-4 was shot down in 1965, and was awarded the Medal of Honor for the leadership he provided to the POWs. After retirement, he was president of The Citadel from 1979 to 1980, and ran for vice president on Ross Perot’s independent ticket in 1992.

The example of courage and fortitude displayed by Stockdale to his men was indeed personal heroism, but it led to something bigger than one man. And that is something Joe Long will emphasize in his address. He will talk about teamwork and mutual support – the way all the prisoners under Stockdale “looked out for each other.”

Kept isolated, they had to invent a way to communicate. They created a unique code, tapped out to each other through the cell walls. It wasn’t Morse Code, because “Morse was a little too slow for the furtive messages that they were sending,” says Joe. He will talk about how that worked in his lecture.

They also had to develop something even more difficult – a new code of honor for American POWs. The old rule of refusing to comment beyond the famous “name, rank and serial number” would not work when held by an enemy who would relentlessly torture every prisoner, for years and years on end.

The U.S. military had learned in Korea that the old way didn’t always work. The prisoners in Hanoi had to find a new way to approach their predicament. Eventually, “The code within the Hanoi Hilton assumed that everyone breaks, so your job was to build yourself back up to resist again, so they had to do it all over.” Then, the men had to “continue resisting as long as they could, despite being completely helpless,” with no end in sight.

Joe will talk, of course, about Sen. John McCain, the Hanoi prison’s most famous inmate and the 2008 Republican nominee for president. He will also tell about POWs other than Stockdale who had South Carolina connections, including:

Jack Van Loan – Although he was born in Oregon, Van Loan retired from the Air Force here in Columbia, where he became a community leader best known for directing the annual St. Patrick’s Day festival in Five Points. Long before that, on May 20, 1967, his F-4 Phantom fighter was shot down over North Vietnam. He ejected successfully, but injured his knee when he hit a tree on landing. After he was captured, “they worked on my knee pretty good … and, you know, just torturing me.” He would be in the hands of the enemy for almost six years. A mural in the museum exhibit celebrates his joyful return.

Quincy Collins – Another Air Force pilot, he was born in Winnsboro and graduated from The Citadel. He was shot down in 1965, and underwent “horrendous torture” until the North Vietnamese eased up in about 1970. He had sung in the choir at The Citadel, and when his captors asked him to put together a choir for a public Christmas event in Hanoi, he did so. The Americans sang “O Holy Night” – but with the words changed to tell the folks back home how thing really were. His POW uniform is on display at the museum.

Joe Long has worked at the Relic Room since the turn of the century. He holds a master’s degree from Georgia College and State University. He’s been published in “Civil War Historian” and other journals, and has co-written some of the museum’s exhibits. He and his wife live in Cayce, and they have six grandchildren.

Comments are closed.