Moss Blachman looks every bit the academic he has been for nearly a half-century, but one thing stands out: His suit coat usually features a small Bronze Star lapel pin. He is proud of his service as an Air Force intelligence officer in Vietnam from September 1965 through the next September.

He’ll talk about it in some detail in a free lecture at noon on Friday, May 17, at the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum in Columbia. The program, “Air Force Intelligence in Vietnam,” is open to the public, and is presented in connection with the museum’s sprawling, unique exhibit, “A War With No Front Lines: South Carolina and the Vietnam War, 1965-1973.” It is part of the museum’s regular Noon Debrief series.

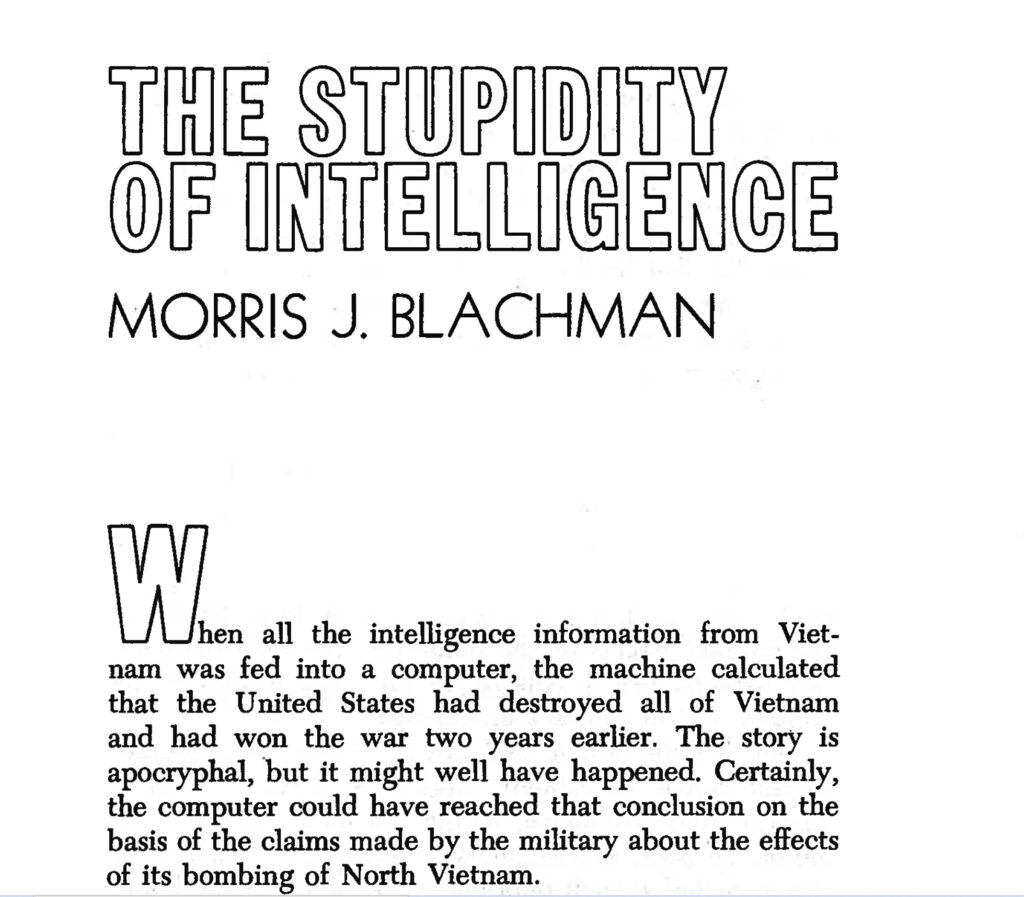

While he is proud of that service, in 1969 he would write an article for Washington Monthly called “The Stupidity of Intelligence,” about how the public got exaggerated reports on the effectiveness of the bombing in Vietnam.

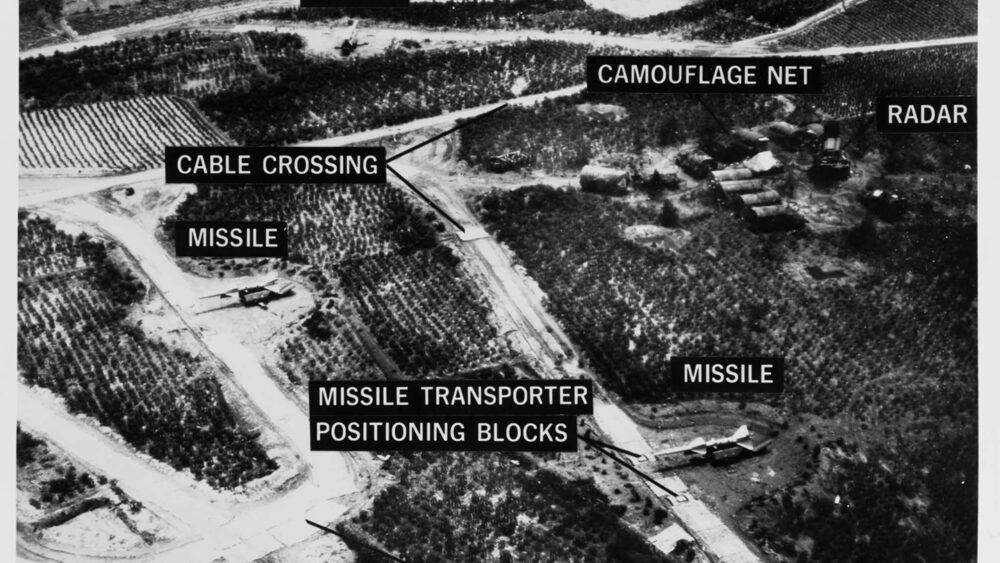

He stressed that that was not the fault of the people he served with directly: “No one, at least no one around me, was systematically lying about the bombing.” He insists the intel guys got it right, but their numbers were always lower than what the pilots reported. This was understandable, since the pilots only got a momentary glance, and the intel folks studied after-action aerial photos.

The problem was, the pilot guesses came in first, and that’s what went up the chain and back to Washington.

Near the end of his Vietnam tour, a senior officer he respected urged him to stay in and make the Air Force a career, and Moss declined. He had not liked a lot of things he had seen during his tour. While he has great respect for most of the men he worked with, there were exceptions. One of them was a captain to whom he reported. Here’s an example of why:

“We had had a few days where the target list was the same,” Moss remembers. One day in the 6 a.m. briefing, the general asked, “Are there any other targets that might be worthwhile?” That afternoon, an order came down to come up with 10 or 12 new ones. But there were “no targets on the intel we had. There was nothing.” Just a bunch of villages, he says.

He had a long day, and at maybe 1 a.m., Lt. Blachman went to the Officer’s Club for something to eat. He had had no dinner. He left his tech sergeant in charge. When he came back, the sergeant was “visibly shaken up.”

The captain had dropped by and asked about the new targets, and was told there were none. He demanded to see the aerial images of the area. “What about that?” he said, pointing.

“That’s a village,” said the sergeant. “You mean, ‘suspect military supply storage area,’” said the captain. He then went on to make the same ruling on several other sites. The sergeant knew “This was the wrong thing to do, but as far as he was concerned, he had been ordered to do it.”

“I agreed with him unequivocally,” Moss remembers. “These were villages, not targets.” So he told the NCO, “I am your superior officer and I am ordering you directly not to do this. I will take full responsibility for that.”

As for the captain, “He never said a word to me.” But Moss often thinks about the villagers who are alive today, and wouldn’t be had the captain been obeyed.

He’ll talk about a lot of other things, such as:

- How it felt to arrive in-country, arriving after more than a day without sleep, and seeing the tracers streak by the plane as it was landing.

- The time he briefed Gen. William Westmoreland, and how that led to a worldwide change in an intelligence protocol.

- His visit to the Continental Hotel in Saigon, when he saw the “war correspondents” drinking gin and tonics and writing their reports based on briefings at MACV headquarters. He contrasts those hacks with the many correspondents who got out in the field and wrote about the actual war.

Comments are closed.