Few of us are experts on the Vietnam War, but most of us have heard that perhaps the greatest flaw in the way the United States conducted it was that military higher-ups in Saigon collected, believed and passed to Washington information that indicated the fight was going better than it was.

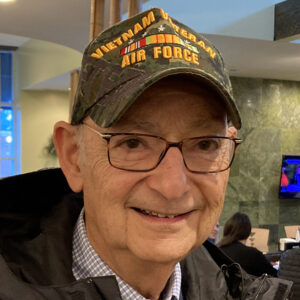

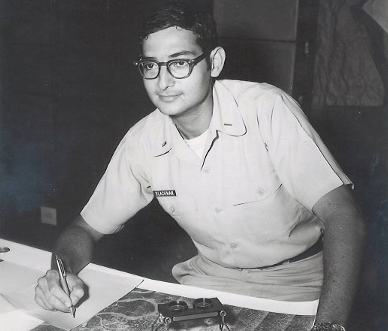

As a young intelligence officer on the ground at the time, Moss Blachman had an intimate knowledge of that process on the front end. At noon on Friday, Feb. 14, he will share what he knows in a free lecture at the Richland Library main location on Assembly Street in Columbia. His program, “Air Force Intelligence in Vietnam,” will be presented in the library’s Theater.

The former Air Force intelligence lieutenant has been processing what he learned ever since he came home in 1966. In 1969, he wrote an article for Washington Monthly, which began:

When all the intelligence information from Vietnam was fed into a computer, the machine calculated that the United States had destroyed all of Vietnam and had won the war two years earlier. The story is apocryphal, but it might well have happened. Certainly, the computer could have reached that reached that conclusion on the basis of the claims made by the military about the effects of its bombing of North Vietnam.

The article was headlined, “The Stupidity of Intelligence.” But that’s not because Moss, or the people who worked with him, were stupid or in any way neglected their duty as aerial photograph analysts. He is proud of his service to his country and has every reason to be, as anyone can tell by the Bronze Star lapel pin that he regularly wears on his civilian jackets. As for his comrades, “No one, at least no one around me, was systematically lying about the bombing.” They did their jobs, and they got it right.

The trouble was, their assessments weren’t passed immediately to the top brass in Saigon, or to Washington. The people in charge were too impatient. They based their decisions on the sketchy post-mission debriefs of pilots, who – while hurrying away from the targets as they dodged enemy fire – only got a momentary glimpse, before the smoke had cleared, of the damage they had caused on the ground. That was available well before the careful analyses of aerial photographs. And the war was guided by the overly optimistic information that came in first.

Moss performed his duties in a manner that impressed his superiors, or at least some of them. But when one senior officer urged him to stay in the Air Force and pursue a career after his tour in Southeast Asia, he declined – largely based on his impression of some of the other officers his served under.

There was, for instance, a captain to whom he reported. When a general asked why there were no new targets on the daily bombing list, the captain ordered his people to find some. When told by a sergeant that there were no other suitable targets at that time – just a few villages – the captain took his own look at the images, pointed and said “What about that?”

“That’s a village,” said the sergeant. “You mean, ‘suspect military supply storage area,’” said the captain. While Lt. Blachman was at dinner, the captain ordered the sergeant to put that and several other villages on the next day’s target list.

When Moss came back from eating, he told the NCO, “I am your superior officer, and I am ordering you directly not to do this. I will take full responsibility for that.”

He never heard anything from the captain, but he often thinks of the people in that village who are still alive today, and would not have been if the captain had had his way.

This lecture was presented last year at the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum. This one is also part of the museum’s regular Noon Debrief program. Those lectures are being presented at the library temporarily because the space at the museum is undergoing renovation, and the library has generously offered its excellent offsite venue.

Comments are closed.