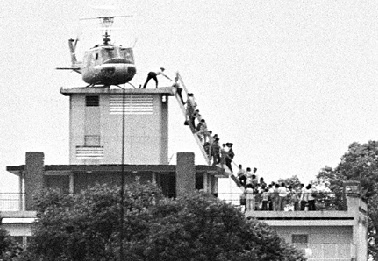

We all remember – if we’re old enough – the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, particularly the image of that helicopter trying to evacuate people from a rooftop. The next day, May Day, the triumphant North Vietnamese declared the formation of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Millions of people’s lives would never be the same again, from Americans who had served in that war to the far vaster numbers of South Vietnamese who had fought alongside them – a population that included the Boat People who desperately fled the country, those who managed to make new lives in America, and the many who remained to adjust to life under the new regime.

On the 50th anniversary of that May Day – May 1, 2025 – Joe Dunn, the Charles A. Dana Professor of History and Politics at Converse University, will speak about how that fall affected one particular subset of Vietnamese in the South – the Montagnards. He will do so in a free lecture at the Richland Library main location on Assembly Street in Columbia at noon on that Friday. The lecture is part of the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum’s regular Noon Debrief program.

In fact, he will focus in particular on one Montagnard named Kok Ksor, who ended up coming to South Carolina, settling in Spartanburg, and spent the rest of his life advocating for his people as leader of The Montagnard Foundation, Inc.

Montagnard is the name used to collectively refer to a number of aboriginal tribes that have never really considered themselves Vietnamese, while the Vietnamese have also viewed them as a people apart. That was true before and after America’s war in Southeast Asia, and it’s still largely true today.

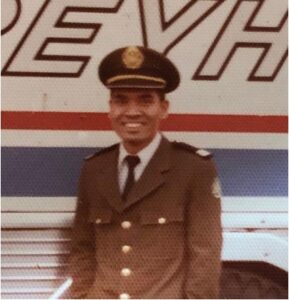

Kok Ksor was a member of the Jarai ethnic group. Many of his people, along with other Montagnards, fought alongside the Green Berets in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. He himself left school at the age of 14 to become a full-time soldier. That was several years before most Americans had heard of Vietnam.

In 1964, the Green Berets worked to bring together the Montagnards and other ethnic minorities into the Central Highlands Defense Force. Another ethnic alliance formed that same year in Cambodia would play a larger role in Ksor’s life. It was the United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races, better known by its French acronym, FULRO.

Ethnic tensions were so high during the war that both the Viet Cong and the South Vietnamese government sought to kill Ksor. On at least two occasions, he was protected by Americans.

As other South Vietnamese who came to America worked to assimilate, Ksor continued working to protect the human rights of Montagnards back in Vietnam and Cambodia. This earned him the brand in those countries as a militant, even a terrorist. Joe Dunn strongly rebuts that impression in a published article about Ksor:

Kok Ksor devoted his entire life to the struggle for human rights and religious freedom for the Montagnard people of the Central Highlands in Vietnam and Cambodia. The story of the dramatic history of these tribal peoples caught in the midst of war and its aftermath and the continuing oppression of a largely forgotten people is conveyed through the career of this extraordinary military warrior, activist, international human rights spokesman, and religious leader. Maligned by the government in power in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Kok Ksor is totally opposite of how the regime characterizes him.

Ksor, a devout Christian, died in South Carolina in 2019. Joe Dunn never met him, but has gotten to know members of his family.

Prof. Dunn is a Vietnam Veteran who has made the war a particular focus of his academic career. He has just returned from delivering a lecture at the Vietnam Center Conference at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas, on “The 50th Anniversary of the End of the War in Vietnam.” He also has been interviewed by the Montagnard Channel, which will air the interview soon on YouTube.

He spoke at the Relic Room in 2023 about his own service as an American soldier in Vietnam.

Comments are closed.