If you’re of a certain age, you may recall a silly comedy film from 1965 called “Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines.” It made slapstick fun of man’s often improbable early attempts to conquer the skies.

But in real life, there were men in the first part of the last century who took deadly serious chances to achieve critically important objectives, particularly during the First World War. They did it riding in both rickety winged machines and various kinds of balloons and blimps. Some of the most daring of them were from South Carolina, and they were quite magnificent.

At noon on Friday, Jan. 31, at the Richland Library main location on Assembly Street in Columbia, Joe Long, curator of education at the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum, will tell about them and their deeds in a free lecture titled “Iron Men and Canvas Wings.”

The lecture is part of the museum’s regular Noon Debrief program. Those lectures are usually presented at the Relic Room itself, but since the space at the museum used for such live programs is undergoing renovation, the nearby library has generously offered a venue for these programs off-site.

The program will focus in particular on several South Carolinians who blazed trails into the air in their own different ways, such as:

Elliot White Springs – When aviators are celebrated, the glory tends to shine most brightly upon the fighter pilots, and Springs was the very epitome of the flying ace in World War I, shooting down 16 enemy aircraft from such legendary biplanes as the Sopwith Camel. He was also shot down more than once himself. Personally, he is probably best remembered today as the owner and boss of Springs Industries, which he inherited in 1931 after his father’s death. But even in civilian life, he cut a daring figure completely consistent with the “knight of the air” image he had helped create.

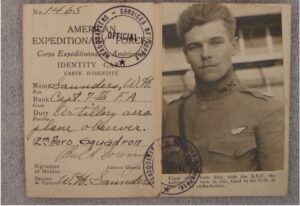

William Harrison Saunders – His job lacked the flash of the fighter pilot’s, but Saunders was a pioneer of something of critical military importance – close air support. His role was to climb into the air and provide real-time intelligence to artillery on the ground, identifying enemy targets from above. He did this with a newfangled “wireless telegraph.” He gave directions in Morse code to the gunners, and if that failed, fly back and drop notes to them. The danger he faced was equal to that of the fighter pilots. He had three airplanes shot out from under him in one day. He received the Distinguished Service Cross, and Shaw Air Force Base would almost be named for him.

William Harrison Saunders – His job lacked the flash of the fighter pilot’s, but Saunders was a pioneer of something of critical military importance – close air support. His role was to climb into the air and provide real-time intelligence to artillery on the ground, identifying enemy targets from above. He did this with a newfangled “wireless telegraph.” He gave directions in Morse code to the gunners, and if that failed, fly back and drop notes to them. The danger he faced was equal to that of the fighter pilots. He had three airplanes shot out from under him in one day. He received the Distinguished Service Cross, and Shaw Air Force Base would almost be named for him.

James Franklin Griffin – Chief Quartermaster Aviation Griffin was a native of Columbia who joined the Navy and volunteered for airship duty, which meant guiding a huge blimp through the heavens. He was the “altitude pilot” on airships charged with spotting German U-boats. He experienced combat, but also performed such extraordinary missions as escorting President Woodrow Wilson’s ship to France for the peace conference to end the war. Unlike planes, airships could slow down to the speed of the ships they were protecting, and stay with them for long periods of time because they did not have to return to base to refuel. He received the French Croix-de-Guerre after a harrowing flight during which he had to crawl out of the gondola and along the gasbag with a wrench to fix a valve that was not responding to controls. He saved 11 men, thousands of feet up, with no parachute.

James Franklin Griffin – Chief Quartermaster Aviation Griffin was a native of Columbia who joined the Navy and volunteered for airship duty, which meant guiding a huge blimp through the heavens. He was the “altitude pilot” on airships charged with spotting German U-boats. He experienced combat, but also performed such extraordinary missions as escorting President Woodrow Wilson’s ship to France for the peace conference to end the war. Unlike planes, airships could slow down to the speed of the ships they were protecting, and stay with them for long periods of time because they did not have to return to base to refuel. He received the French Croix-de-Guerre after a harrowing flight during which he had to crawl out of the gondola and along the gasbag with a wrench to fix a valve that was not responding to controls. He saved 11 men, thousands of feet up, with no parachute.

Hear these stories and more, at Richland Library on the 31st.

Comments are closed.