One of the biggest obstacles the U.S. military services faced in Vietnam was that posed by Mother Nature – the lush, tropical rainforest that never stopped growing. It impeded movement, and provided millions of hiding places for enemy troops bent on ambush.

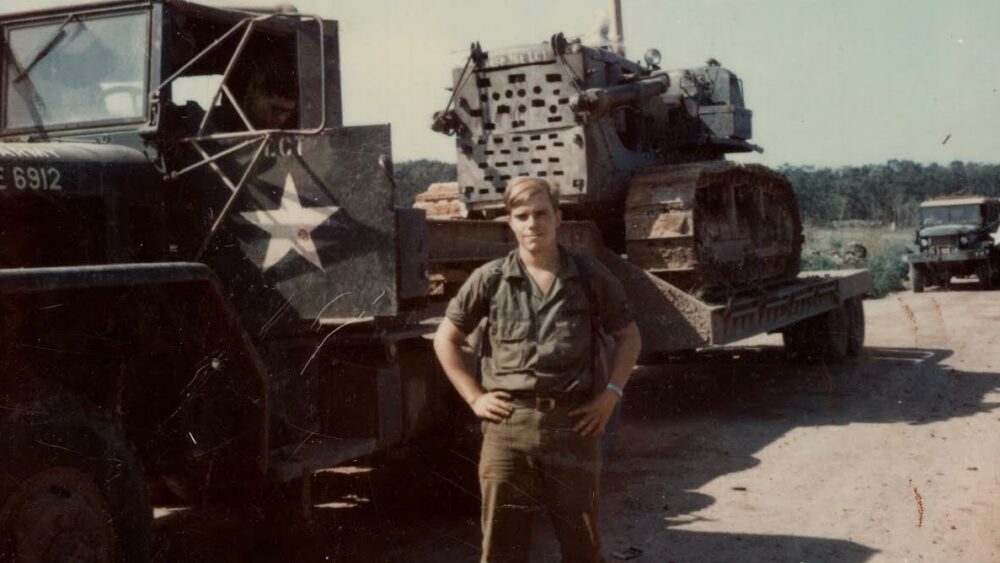

Keith Albert of Florence was one of the people assigned to deal with that problem. He was a mechanic with the 86th Engineering Battalion, which operated out of Bearcat Base near Biên Hòa, South Vietnam. He was out in the field keeping the heavy machinery running – the machines that mowed down the jungle, day after day – for most of his tour in Vietnam, which started in late 1967.

Albert will tell his war stories in a free lecture at noon on National Vietnam Veterans Day – Friday, March 29 – at the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum in Columbia. The program, “Land Clearing in Vietnam,” is open to the public, and is presented in connection with the museum’s sprawling, unique exhibit, “A War With No Front Lines: South Carolina and the Vietnam War, 1965-1973.” The lecture is part of the museum’s regular Noon Debrief series.

The 86th wasn’t the unit Albert was assigned to when he arrived in-country, but he was sent out to join it in the jungle for a 90-day stint in November 1967 – and didn’t return to his assigned unit until a few days before his year-long tour ended. The primary challenge for him and the other mechanics was keeping the Rome plows and other equipment operating.

The Rome Plow was a large, specially modified armored bulldozer developed specifically for use in Vietnam. The machines were equipped with a very sharp “stinger blade” that weighed more than two tons and was able to cut down entire trees, which were then burned. When fully equipped, a Rome plow tractor weighed 48,000 pounds. They were mounted on Caterpillar D7E bulldozers.

The Rome plows and those who attended them operated under harsh, dangerous jungle conditions, and were assigned a tank platoon and an infantry company for security. That didn’t prevent the operators from becoming casualties.

Not only was the enemy often shooting from the greenery the unit was working to clear, but the plows themselves were dangerous, operating in the uneven terrain. “We lost a lot of operators to roll-overs,” said Albert. Many of them were seriously burned by the acid from the vehicles’ batteries.

The mechanics weren’t safe, either. On his Facebook page is a picture of Albert in 1968 (see below), working on the cage from one of the machines, in which the operator sat while working. He’s having to stand up to work, because of stitches in his leg from a recent bullet wound.

He has a lot of stories to tell. Join him on March 29 in the Education Room at the museum.

Comments are closed.