Tommy Cockrell didn’t set out to serve with the Army engineers in Vietnam. His training was in combat infantry. But when he arrived in-country, that’s where they sent him.

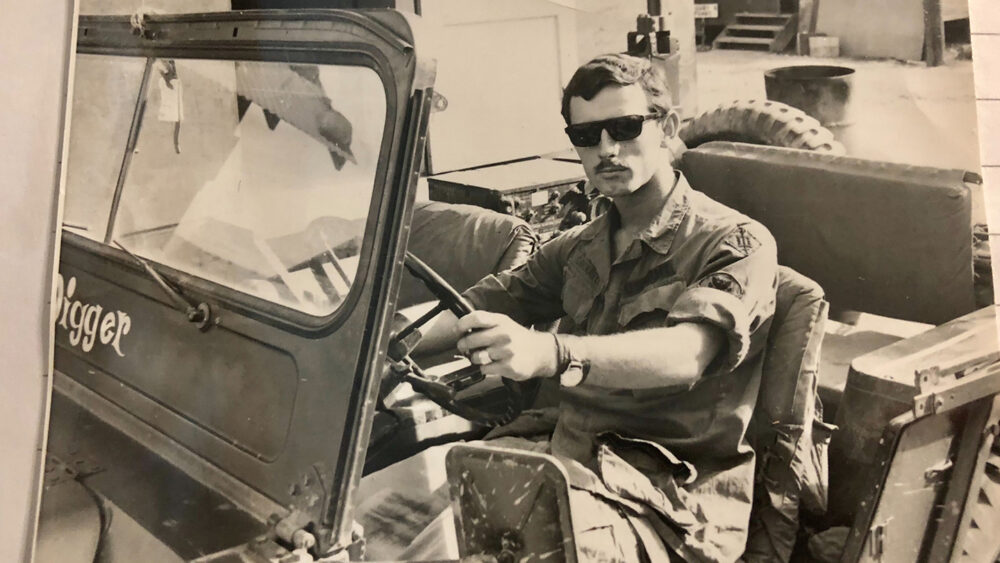

So it was that he found himself driving – often alone – up and down the perilous roads of I Corps, with no protection but his M-16 and maybe a sidearm, through Huế and other places that had seen some of the worst fighting of the war.

He’ll tell his story in a free lecture at noon on Friday, Nov. 10, at the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum in Columbia. The lecture is open to the public as part of the museum’s regular Lunch and Learn series.

Tommy was born in Columbia and largely grew up in nearby Camden. In preparation for the call from Uncle Sam that was inevitable for a young man in 1969, he reported for a physical. Although “I’m basically blind in my right eye,” he was judged fit for duty. He decided to volunteer for the Navy.

That was the plan, anyway. “Before I could go in, I got my draft notice.” He had a choice, though: Two years in the Army, or four in the Navy. He went for the shorter hitch.

After basic and infantry training at Fort Jackson, he was off to Southeast Asia, where he was assigned to the headquarters of the 14th Combat Engineer Battalion. It wasn’t a combat assignment, but it was certainly in a combat area – at Firebase Nancy in I Corps, just about 17 miles south of the DMZ. That is, about 17 miles south of North Vietnam.

The 14th, which was there to build roads, bridges, firebases and other projects requiring heavy construction equipment, shared Nancy with “an artillery unit that was doing live missions day and night,” and a South Vietnam Army outfit. It wasn’t the greatest place to be, but “It was a lot better than what I had thought I was going to do.”

He wasn’t trained as an engineer, but they found plenty for him to do. He spent his first months out on the lonely road. First, he was assigned to drive a deuce-and-a-half the 14 clicks to Quảng Trị to pick up the mail, and bring it back to Nancy to distribute to everyone stationed there. As with armies throughout history, “Mail call was a popular time.”

After a few weeks of that, he got a longer and lonelier assignment, driving a Dodge M37 to the group headquarters, 35 miles away at Phu Bai. Then he’d bring back correspondence, supplies, and sometimes people who needed to go to Firebase Nancy. That took him through Huế, which was still seriously damaged from the fighting during the Tet Offensive the year before. The city was “extremely crowded” with heavy traffic in the 5 mile-per-hour range.

His 70-mile round trips were “not necessarily the safest thing,” especially when he didn’t have anyone riding shotgun. After a couple of months, he’d had enough of it. An opportunity came to make a change. “One of the guys in the hooch one night was talking about how he hated being around the colonel” and other brass working in the headquarters office. So they got permission to switch.

“I got off the road and he got out of the office.” He learned a lot working with the lieutenant colonel and other officers. Like with anything else, the job had its good parts and bad parts. “One of the most satisfying” duties was to process medals for his comrades, and see them receiving their recognition. He handled about 500 of them.

The worst part was typing letters home to families telling them how their loved ones had been killed. The colonel wrote them out longhand, and Tommy did the typing. There weren’t as many of these as there were commendations – “maybe 10-15 KIAs” – but there were still too many.

Tommy had arrived in Vietnam in October 1969, and didn’t go home until November 1970. That’s because he had volunteered to extend his tour in exchange for an early discharge from the Army.

He was discharged as an E-5, and went back to work at the textile plant in Bishopville where he had been before the Army. Not long after that, he took a job at a local hospital in Camden, and ended up working in health care for the next 47 years. He also went to college on the G.I. Bill. The last 25 years of his career were spent at the South Carolina Hospital Association, from which he retired as president of the organization’s for-profit division.

Comments are closed.